The Life and Works of Rumi

Rumi lived from 1207-1272. The majority of his life was spent in Konya, Turkey, then known as Rum. He was a teacher and spiritual leader, an Islamic authority on the Quran and the Hadith, beloved by those from all walks of life, including royalty and paupers, other scholars and the clergy of all religions. Rumi’s two most famous works, The Mesnevi and the Divan-i Kebir are in poetic forms, and their sheer volume is astounding. Our focus is on the poetry in his Divan-i Kebir, which includes over 44,000 couplets. His other works include: Mesnevî (6 volumes of stories and anecdotes, approximately 24,000 couplets all in one poetic meter). Mektubat (letters), Mecâlis-I Seb’a (seven sermons), and Fîhi Mâ Fîhi (conversations).

Shams of Tebriz

Rumi has given the world literally tens of thousands of verses of inspiring love poetry. As is well-known, the life-changing event most responsible for this prolific output is his meeting in 1244 with Shamseddin (Shams) of Tabriz (1185-1248). The two spent less than three years together, yet Shams was able to transform Rumi into an ecstatic lover of God, In the words of Rumi,

“O Beloved, when Your Love flared up in my heart,

everything else was burned to ashes.

My heart put my mind, books and lessons on a shelf

and replaced them with verses, odes and quatrains.”

(The Rubaiyat of Rumi, The Ergin Translations, Volume 1, Rubai 362).

The Role of Islam in Rumi’s Life

Rumi was born in the Islamic tradition, so we would expect his poetry to reflect that, and it does so beautifully. As he says in one of his quatrains,

As long as my soul stays in my body,

I am a slave of the Quran and the dust on the path of Muhammad.

If anyone interprets my words differently than then this,

I will break with him and reject his words.

The Rubáiyát of Rumim The Ergin Translations, Volume 2, Rubai 735.

However, Rumi’s message is universal. His Islamic roots do not change his appeal for those of all religious backgrounds, nor do they diminish the existence of other messengers of God from other religious traditions and the Truth of their messages. He clearly states in a quatrain:

There is neither question nor answer on the way to Love,

but only a mystery.

The lover never answers to any human orders.

This is a matter of Absence, not existence.

The Rubáiyát of Rumi, The Ergin Translations, Volume 3, Rubai 1314.

The Role of Music in Rumi’s Life

Rumi introduced “turning” accompanied by music to his disciples in a ceremony known as Sema. During the ceremony, participants allowed the music and their turning to carry them into an ecstatic state. Because of the practice, after Rumi’s passing and with the formal organization of the Mevlevi Order of Sufism by Rumi’s son, Sultan Veled, members of the order were and are still known as the Whirling Dervishes. According to Dr. Erdoğan Erol in his publication, Mevlânâ’s Life, Works and The Mevlânâ Museum, Turkish scholar Abdülbakî Gölpinarli reported, “Mevlânâ would easily be impressed by daily events and would start reciting his feelings while he was performing sema in ecstasy and pour them into the mould [sic] of measure and rhyme.” (Drawings by Smaro Grigoriadou)

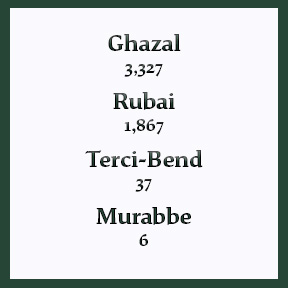

The Forms of Rumi’s Poetry

There are four forms of poetry in the Divan-i Kebir: the ghazal, the rubai, the terci-bend, and the murabbe. (Click on each link to see an example of the form.) The translations of each of the four forms presented are from Nevit Ergin’s translations of the Dîvân-i Kebir. You will note that Ergin does not translate word-by-word, nor does he use rhyming or follow Rumi’s couplet format. What he does do is capture the essence of Rumi’s poetry brilliantly.